“It is noteworthy that the model for the King’s action is Greek. Luminalia also had a Greek component in that one of the minor themes dealt with the expulsion of the Muses from Greece and their eventual settlement in Britain. Greece signified culture in contrast to Rome with its associations with military and imperial might.”

– Graham Perry, The Golden Age Restor’d: The Culture of the Stuart Court 1603-42, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1981, p. 202-203.

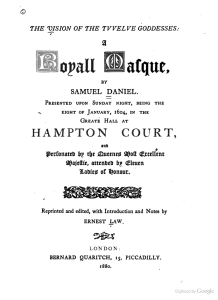

Upon reading the above quote in Graham Perry’s work on the Stuart masques, it really got me thinking of Queen Anna’s first public masque, The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses by Samuel Daniel and designed by Inigo Jones. Even though the quote is in reference to the Caroline masques and not the Jacobean ones, it is an interesting framework to examine the assignment of roles in the masque. Performed in 1604, it was the first masque of Anna’s career as Chief Masquer (not Blackness by Ben Jonson in 1605 as Perry asserts). Below I have compiled a chart of who danced with Anna in the masque and what persona they embodied. This is an appendix taken from a paper I wrote up as a thesis of sorts to complete a directed study. In the scope of this post, I’ll just be looking at the role that Anna took, rather than the ones that were assigned to her Ladies of Honour. I hope to, at another juncture, have the opportunity to look even deeper at the masque and analyze the iconography and symbolism in the text and device.

| The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, by Samuel Daniel | |

| Name/Rank | Role |

| Queen Anna | Pallas Athena |

| Countess of Suffolk | Juno |

| Countess of Hertford | Diana |

| Countess of Bedford | Vesta |

| Countess of Derby | Persephone |

| Countess of Nottingham | Concordia |

| Lady Rich | Venus |

| Lady Hatton | Macaria |

| Lady Walsingham | Astraea |

| Susan de Vere | Flora |

| Dorothy Hastings | Ceres |

| Elizabeth Howard | Tethys |

I’ve gone through and done a simple sorting scheme – Red = Roman, Green = Greek. The role that Anna chose for herself was quite significant in terms of how she wanted to be perceived and was an effort in self-fashioning her public identity. Instead of choosing the role of the Roman Queen of the Goddesses (well, Queen Consort!), Juno, she gave that role to Catherine Howard, the Countess of Suffolk. Suffolk had served Queen Elizabeth for many years and was a person Anna respected and trusted, as is evidenced by the fact that Suffolk had been chosen to be godmother to Anna’s daughter, Sophia. Anna accorded Suffolk with a very high honor in placing her as the queen of the goddesses. Her choice for herself was Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, battle, and the arts.

Athena was also the patroness of the City of Athens, which was named for her. An ancient cosmopolitan centre, Athens was home to a bustling arts and culture scene and has typically been regarded as the birthplace of western civilization as we know it.

Perhaps Anna’s motive was to seize a new image for herself, one that reflected virtues that she wanted others to think she possessed, or ones to which she did lay rightful claim? Perhaps her choice of Athena was a chance to scintillate and titillate the English and to show that she was a very different sort of Queen consort? The last queen consort, Katherine Parr, was also a very literary woman who published popular works in her own name while she was Queen. Anna didn’t create written works on her own, she was more of an idea lady who directed the works of others. It was through those works though, that the image that Anna wished to portray comes out clearly. In Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, as Athena, her persona was of a strong, wise female who held dominion over Athens. Her costume included a short tunic (that bared her legs below the knee) and a helmet with a spear.

Anna’s husband, James, dearly held to the ideal of pacifism and detested using force and military might. With her act of appropriating the weaponry and tools of war, Anna took on a more traditionally masculine role in their perceived relationship and set herself up as a worthy successor of Elizabeth I. Which was a prudent act to take as the costumes were also from Elizabeth’s wardrobe. As a cost saving measure, the Late Queen’s wardrobe was raided for her sumptuous gowns and the garments altered to be fit into appropriate costumes for the masque.

(“I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.” ~excerpt from Elizabeth’s speech at Tilbury, 1588)

Looking to the quote at the start of the post, however, it is interesting that Anna chose Athena instead of Minerva. Minerva, Athena’s Roman counterpart, would have more exemplified the Early Modern interpretation of the Roman empire, one of peace loving imperialism, instead of the Greeks, who demonstrated the aforementioned arts and sophistication. Anna, then, presented a dual image. With choosing the Greco-interpretation of Athena, she sided herself with the perception of culture that was generally accepted to have belonged to the Greeks. Perhaps she was trying to conflate the new dynasty with a rebirth of Athens. With choosing Athena, though, she also personified the militaristic might of the Goddess of War, tempered, of course, with Wisdom.

In so doing, Anna managed to display both the sophistication of the Greeks with the imperialistic might of the Romans, subtly reminding the attendees of the virtues of Pax Romana and the olive tree of Athens.