A few years back in 2011, I’d been laid off from my job teaching science to children in a museum and ended up through a confluence of random events living that summer on a small farm near Grinnell, Iowa. That summer was full of unfortunate firsts – unemployment, accidental vehicular homicide of pets, learning how to wrangle calves back to their disgruntled mums. Oh, and my beloved dwarf hotot, Joss, died. There are a lot of things about that summer that while I don’t regret, I certainly wouldn’t like to live over again.

I spent a lot of time by myself that summer as my partner had gotten a job about an hour away working as tech support in a localish school district. Internet connection at The Farm was spotty at best and I was generally pretty isolated. We’d adopted a couple of farm kitties as friends, but the owner of the house said that they had to stay outside. We basically got to feed them, but other than that they were left to fend for themselves. I was never happy about that situation. One, who I named Marlena since she looked like a glamorous little movie star, loved to follow me around as I walked in the humid Iowa heat to explore my surroundings. The other was accidentally killed when I decided to go and pick up pizza in town. RIP Richie.

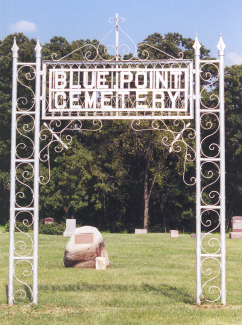

Marlena, my constant companion, and I would take walks around the little wooded area that was near the farm house, and one day I happened a pioneer cemetery. I found out that The Farm was nearly equidistant to TWO pioneer cemeteries. These cemeteries serviced the town of Blue Point, Iowa, from the mid-nineteenth century until at least the turn of the century. Also – in Iowa, “pioneer cemetery” doesn’t just mean that pioneers are buried there. The cemetery also has to have had “fewer than twelve burials in the last 50 years.” So, these were definitely pioneer cemeteries! My inner historian’s brain kicked in and I immediately turned to genealogical records to find out about who these people had been and how the ended up here of all places.

I was drawn first to the memorial belonging to Elizabeth McNabb – not only was she a young woman at her death, 26 years old, she was also the first to be interred in the Lower Blue Point cemetery. I’m not sure why I gravitated to her stone, maybe it was because I had just turned 27 myself, but I wanted to know more about this young woman who now lay between farm fields in the middle of rural Iowa. I figured I probably wouldn’t be able to find much, but any bit of remembering, I think, is appreciated by the universe.

Doing a bit more digging, pun not intended, I also found the grave markers of her husband, William McNabb, in the Lower Blue Point cemetery and her parents, Levi Carpenter and Susannah Moore Carpenter, in the cemetery just down the road, the Upper Blue Point cemetery.

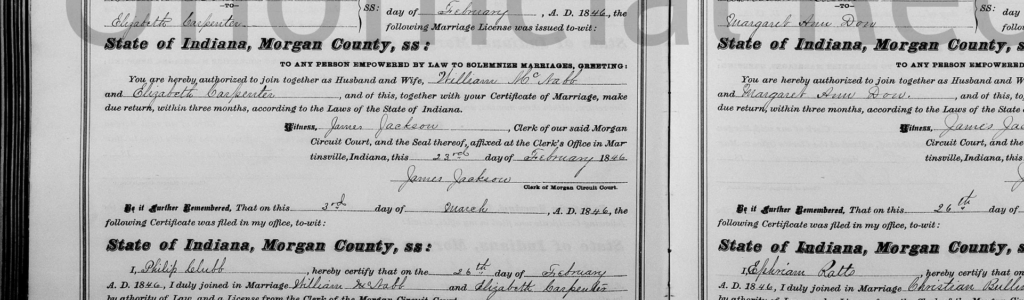

There isn’t much available online about Elizabeth herself, but I was able to find her marriage certificate to William, and a bit more about her husband.

So, Elizabeth Carpenter married William just after she turned 15 years old. They had their first child, Eliza Ann, in early 1848. Sometime before their second child, Susan Jane, was born in 1850, William and Elizabeth had moved to Poweshiek County in Iowa. All of their subsequent children, including Susan Jane, had been born in Poweshiek County. They’d been there long enough to be established into township leadership as William was appointed as a township trustee in 1852 after having run for the Justice of the Peace position and losing by three votes.

Elizabeth may have been motivated by strong religious beliefs as in 1852 she herself pops up in the history of Blue Point (although not by name). “Among the charter members of the [Methodist Episcopal] church were R. C. Carpenter and wife and William McNabb and wife” (Leonard Fletcher Parker, History of Poweshiek County, 286). This also is an interesting point – the R. C. Carpenter was Elizabeth’s brother, Robert Campbell, who had moved with their parents, Levi and Susannah nee Moore Carpenter, to Poweshiek County. Guessing by the dates of birth of Elizabeth’s nieces and nephews, most of the Carpenter family moved to Iowa in 1851. It looks like, as pater familia, Levi Carpenter moved his entire family, including adult children and their families, to Washington Township, Poweshiek County. This may have been why William and Elizabeth settled in Lower Blue Point instead of in Upper Blue Point like the rest of the family did. This way, they were close enough to family that they could help and be helped but also have a degree of independence.

It is probable that Levi was enticed to move out there by Elizabeth and William, as they’d been there since at least 1850 (judging by the birth of Susan Jane). According to History of Poweshiek County, William was a resident of the county since October of 1848. Indeed, he was the first resident of the county (although I assume that Elizabeth and their children were a major part of that!).

The first church/schoolhouse in the township, the Methodist Episcopal church I just mentioned, was built on land originally owned by William and Elizabeth which they sold to Bartholomew Vestal, a preacher who moved to the township in 1853, for $1. It is a rather unfortunate turn of events that Elizabeth was the first to be interred there.

I have not been able to find an obituary which lists her cause of death, but my guess is complications following childbirth. Her final child, Sarah Elizabeth, was born on May 29, 1857, just a couple of weeks before Elizabeth died on June 12, 1857. All in all, she gave birth to at least four children, all of whom survived to adulthood.

William very quickly remarried to Sarah Elizabeth Vestal, daughter of Bartholomew Vestal (who was one of the early preachers in the Methodist church). They didn’t have any surviving children together, and William died almost exactly a year after Elizabeth passed, on June 18, 1858 of a lightning strike.

Their orphaned children lived with nearby maternal relatives, many of them staying in the area until their own deaths.

The church and schoolhouse, built on their land that they sold to the Vestals, was later moved bit by bit into the Heritage Park in the nearby town of Grinnell in 1990.

Little Marlena and I continued to visit the Lower Blue Point cemetery for the rest of that summer, until her unfortunate death of being run over by a farmer’s truck. We’d begun to catalogue the memorials and to research on the rest of the township, but were stymied by the lack of reliable Internet connection and transportation to the nearby county historical society in Montezuma.

That summer, even though it was my Bad Summer, I learned that maybe, just maybe, I do have what it takes to be a historian. The next year, I went back to school to earn my BS in history, where I worked on German immigrants to the Upper Peninsula, and began down my path of Tudor/Stuart England, which is my main area of research.

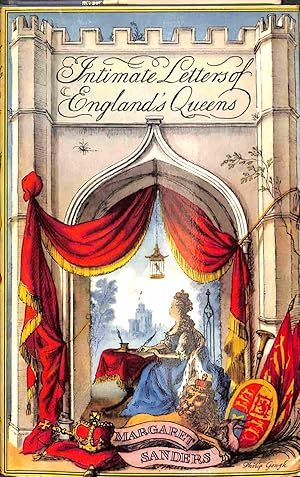

I wasn’t able to find Elizabeth’s voice in my research, just a brief chronology of some of her major life events. Women, especially, tend to disappear into the historical record when they are simply “and wife,” utterly replaceable to the historians who do not value their lives and contributions other than the procreation of heirs to important men. Elizabeth was more than that – and I do hope that someday I’ll get to learn more about her.

And now, I have a kitty who stays inside 100% of the time, so I never have to find my beloved furry friend having lost a battle with a Ford F150.