In which we reach the final episode of our Rose of Versailles series. Thanks for sticking around – and stay tuned for our next series on Victoria! I’ll post the first of series two on the first Friday in November!

Courtney Herber, Ph.D. – Historian

Politics, gender, performance, and theatre in the early modern world

In which we reach the final episode of our Rose of Versailles series. Thanks for sticking around – and stay tuned for our next series on Victoria! I’ll post the first of series two on the first Friday in November!

Rose of Versailles – In this series, we will examine some of the complicated and fascinating history behind the French Revolution and how the 1970s women’s lib movement in Japan influenced the making of the smash hit anime and manga Rose of Versailles!

Let’s talk about Marie-Antoinette and LADY OSCAR!

Whelp. Second podcast out in the world. Let’s keep going! Look out on this space next Friday for the conclusion of the first series: Rose of Versailles!

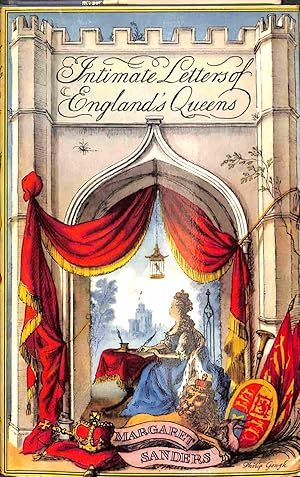

So I finally (well, finally in this age of Amazon prime shipping means a week later) have my hands on Margaret Sanders’ Intimate Letters of the Queens of England (London: Museum Press LTD, 1957), which is the source Patrick Williams pointed to for his version of Katherine of Aragon’s final letter to Henry VIII.

I wanted to follow the clues like a good detective and see where Sanders found HER copy of the letter which she printed in Intimate Letters.

First off – this is a gorgeous old book and you can tell it is meant for a general audience – it says so in the preface. 🙂 Sanders meant to give readers an introduction to these queens as human beings with complicated emotional lives that can’t be distilled down to ‘divorced, beheaded, died…’ and tried to choose letters that display those relationships with others. “Historians must inevitably be prejudiced, either from religious, political, or personal attitudes,” Sanders notes, and then goes on to say that in her introductions to each of the queens and their letters that she just tried to give the bare minimum of factual information, but, like those aforementioned historians, she exhibits her own bias and personal opinions (apparently Henrietta Maria was “the loveliest of all England’s Queens” and Anna of Denmark had “no great pretensions to beauty” but she had a great personality).

This is particularly evident in Katherine’s introduction where she takes at face value Katherine’s virginity going into her second marriage (which, let’s face it, every historian who works on the Tudor period has their own opinion, but it’s far better as a scholar to present it as a complex unknown full of messy political, personal, and religious meanings rather than “In the meantime, this young widow of an unconsummated marriage…” which, technically, if it were unconsummated, it wouldn’t have been a complete marriage, but that’s beside the point).

Sanders includes helpful footnotes to explain who people are and to provide further context when it’s needed for the general audience who may not know who “My Lady of Salisbury” was… although reading through the footnotes, if I didn’t know that Lady Salisbury was Margaret de la Pole, the countess of Salisbury, I’d be further confused – “state-governess to Mary” and “Mary’s best friend next to her mother” are all that’s used to describe who she was. Another confusing point is that Mary I was “brought up in her mother’s Faith as a strict Roman Catholic.” This is certainly true, but it neglects the important consideration that it was also her father’s faith at the time, if you were a practicing Christian at the time, it most likely was your faith as well because the Roman Catholic church was the dominant church in western Europe.

Anywho, after taking the time to peruse the book and finding other fun tidbits that I may post later, I want to give you the transcription of the Final Letter as put in Intimate Letters and then share with you her citation.

My Lord and Dear Husband,

I commend me unto you. The hour of my death draweth fast on, and my case being such, the tender love I owe you forceth me, with a few words, to put you in remembrance of the health and safeguard of your soul, which you ought to prefer before all worldly matters, and before the care and tendering of your own body, for the which you have cast me into many miseries and yourself into many cares.

For my part I do pardon you all, yea, I do wish and devoutly pray God that He will also pardon you.

For the rest I commend unto you Mary, our daughter, beseeching you to be a good father unto her, as I heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage-portions, which is not much, they being but three. For all my other servants, I solicit a year’s pay more than their due, lest they should be unprovided for.

Lastly, do I vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things.

Sanders, Intimate Letters, 12.

And there’s one last bit that I’ve been saving for the end. I had to order another book to dig into this mystery. Most of the documents that Sanders brings together are from the royal archives at Windsor Castle, the Strickland sisters’ work The Lives of the Queens of England, or other letter collections. As a historian, one needs to be a good detective – even though it can take forever and lead you down rabbit holes that go nowhere, at least for the project you’re currently working on – and to be a good detective, one needs to follow the clues.

In Sander’s bibliography, The Final Letter wasn’t cited as from an archival source – it’s from another letter collection.

“Chatterton: Royal Letters” is all we get in Sander’s bibliography to note where SHE got this letter from. So I used my Googlefu and found that this citation refers to Royal Love Letters by E. K. Chatterton, originally published in 1911.

After a little more searching, I found a hardcover copy that will be winging its way to me from England soon. As soon as it does, I will update with more information.

The game is afoot!

S01E01- Rose of Versailles – In this series, we will examine some of the complicated and fascinating history behind the French Revolution and how the 1970s women’s lib movement in Japan influenced the making of the smash hit anime and manga Rose of Versailles!

First podcast – posted. Wish me luck.

Listen up let me tell you a story, a story that you think you’ve heard before…

One of the things that is most fascinating to me in history is all of the things that we just plain don’t know – but sometimes – we think we know. History is, of course, a bit of detective work, a bit of scientific information gathering and positing theses, and a lot bit of writing delicious prose that may have been left in the oven too long and comes out dry enough to gag you like my mom’s Thanksgiving turkey.

Now, I work in the early modern period, which is generally understood to have started after the end of the medieval period but ends before the really modern modern period. Got that? Not confusing at all, right? Periodization (or the naming and grouping of ‘periods’ together into larger chunks of time) is so fun to me – but in all seriousness, the early modern period looks differently when you’re talking about different places. In England, where we will focus on for this post, the early modern period roughly/exactly starts when Henry VII usurped the throne of Richard III (also known as ‘the Usurper’). So, 1485, at the beginning of the Tudor dynasty’s spin at running England. The modern period typically is understood to begin at the French Revolution as a blanket date, so the early modern period is roughly 1485-1789.

That’s a lot of time to work with. And it happened, well, several centuries ago, and I can’t find the receipt I got from Whole Foods last week, so it’s understandable that letters, documents, diaries, etc go missing from even further back.

Sometimes, historians are lucky enough to actually find documents that have survived in homes, archives, etc, to work with. Like this:

This is taken from inventories of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603)’s household at her funeral and is part of a collected set of documents which describe the materials and costs of those materials needed for her funeral. Having a list of all the people in her household, what jobs they did, and what rank they held was important so that they got the appropriate amount of black cloth to make into clothing for the funeral (as well as any other pensions due to them). So if you’re interested at all in the people who worked Elizabeth’s household on the day to day basis – it’s in here (at least those who were in her employ at her death). This is a pretty fantastic document to have survived four hundred years!

There are other documents which, while the original hasn’t survived, copies of them have. These copies, while they are super helpful still to historians, are more difficult to work with than the originals. Copies, in the early modern period, were all made by hand or by printing and errors could easily creep in during the copying process. So even if we have one copy, it may not tell the whole story and it’s important to find other copies and compare them to one another to see if there are differences and if there are, what are they?

So the point of this post is to look at one letter in particular – Katherine of Aragon’s ‘last’ letter. Supposedly written at the very end of her life to her husband, Henry VIII, it is very much in character for what we know of and believe to be true about Katherine’s attitudes and language usage.

This is believed to be the text of this letter – which you can’t find in an archive, as reported in Giles Tremlett’s fantastic biography of the queen:

My Lord and dear husband,

The hour of my death now approaching, I cannot choose but, out of the love I bear you, to advise you of your soul’s health, which you ought to prefer before all considerations of the world or flesh whatsoever. For which yet you have cast me into many calamities, and yourself into many troubles. But I forgive you all, and pray God to do so likewise. For the rest, I commend unto you Mary, our daughter, beseeching you to be a good father to her. I must entreat you also to look after my maids, and give them in marriage, which is not much, they being but three, and to all my other servants, a year’s pay besides their due, lest otherwise they should be unprovided for until they find new employment. Lastly, I want only one true thing, to make this vow: that, in this life, mine eyes desire you alone. May God protect you.

Tremlett, Giles, Catherine of Aragon: The Spanish Queen of Henry VIII (New York: Walker & Company, 2010), 364.

Tremlett takes this last letter with a healthy dose of skepticism. While it is very much in character for what we as modern readers would expect from Katherine on her deathbed (supposedly she signed it as “Katharyne the Quene”), there aren’t any other corroborating pieces of evidence which make it undeniable that this is the letter she wrote. There’s no mention of it in diplomatic missives – Eustace Chapuys, who was the ambassador from the Holy Roman Empire and Katherine’s nephew Charles V, never mentioned it when writing to his lord. He did write, however, of a request that Katherine made of Henry to take care of her servants after her death (it cannot really be termed a will as at the time English law forbade women from writing wills if their husbands were living – as technically everything the wife owned belonged to the husband).

Knowing that according to English law a wife can make no will while her husband survives, she would not break the said laws, but by way of request caused her physician to write a little bill, which she commanded to be sent to me immediately, and which was signed by her hand, directing some little reward to be made to certain servants who had remained with her.

Eustace Chapuys to Charles V, 21 January 1536.

This is kind of a baller move by Katherine. It shows, one last time, that she never stopped treating herself as Henry’s wife. If she had proclaimed a last will and testament, she would have acknowledged that they were no longer wed, under English law. To her last, she fought to retain her status as queen of England.

Still, though, Chapuys does not mention anything about a last letter to Henry. Chapuys was one of Katherine’s staunchest allies – who fought to protect her rights as queen and her daughter Mary’s status as princess. It would make sense for her to trust Chapuys with the knowledge of such a letter – but there is no mention.

Other scholars take it at face value that such a letter existed – Patrick Williams is one. In his new biography of Katherine, which is exceptionally detailed when it comes to the political intricacies and machinations of the time, Williams writes of Katherine’s last letter as a matter of course – no interrogation of its veracity. His version is different from the one that appears in Tremlett’s biography and I’ve quoted it below:

My Lord and dear husband,

I commend myself to you. The hour of my death draws near, and my condition is such that, because of the tender love that I owe to you, and in only a few words, I put you in remembrance of the heath and safeguard of your soul, which you ought to prefer before all worldly matters and before the care and tendering of your own body, for the which you have cast me into many miseries and yourself into many anxieties.

For my part I do pardon you all, yes I do wish and devoutly pray to God that He will also pardon you.

For the rest, I commend unto you Mary, our daughter, beseeching you to be a good father to her, as I heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage-portions, which is not much, since there are only three of them. For all my other servants, I ask for one year’s pay more than their due, lest they should be unprovided for.

Lastly, do I vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things.

Williams, Patrick. Katharine of Aragon: The Tragic Story of Henry VIII’s First Unfortunate Wife (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2013), 374.

So while they largely say the same things, they do so in completely different tones. One of the jobs of an early modern wife was to guide her husband to godly behavior and choices – which ‘Katherine’ does here in her letters. Tremlett’s letter seems more of the devoted wife- ‘because of the love I bear you’ rather than Williams’- ‘because of the tender love I owe to you‘ which sounds more like an obligation rather than her choice. Although, honestly, I can’t really blame her for treating the performance of love as an obligation to Henry at this point.

Tremlett doesn’t say where he got this particular copy of the letter – but it has been circulating and taken as fact for generations. Williams, though, cites another Amberley publication, that by Margaret Sanders (who Williams names “Saunders” in his bibliography). Now I’ve not gotten ahold of her book yet, Intimate Letters of England’s Queens, but it is on the way, and I will write an update when I have it. I hope that she includes her archives for the letters she edited in her collection which will help bring light to this (or make it even more confusing).

As a historian, I have a hard time saying that these letters are totally fake. I can’t, for absolute certain, say that they are fictitious, but the most important question to me is not whether they are fake or real (which, let’s be real here – is super important) but why they exist at all. Let’s say that they are fake – what story is being told by them? How are Katherine and Henry represented by the story told by these letters? Who benefits from presenting the historical figures in this particular way?

That, my friends, is the subject of another blog post.

Stay tuned! Same bat time, same bat channel. Oh, and Carthage must be destroyed.

This week I have been working hard on studying for the GRE, which has been an adventure in and of itself. Learning more about my weaknesses and strengths as a student and academic is an interesting exercise and has proven to be surprising and difficult. Regardless of my own Sisyphean trials these past couple weeks, I have been working to stay connected, at least marginally, to the community from Kings and Queens 3. One of the best ways to do that has been via Twitter, and from there, I found a fascinating tidbit to share with you today.

Beyond the Dark Ages- A nunnery by any other name

In this post, Sarah Greer give a little information about what she studies, female monasteries. Not nunnery? Well, a nunnery and a monastery were two different things! She does a great job of explaining why she uses the term “female monastery.”

(Image Courtesy of Wikipedia) Statue of Matilda of Flanders

(Image Courtesy of Wikipedia) Statue of Matilda of Flanders

This biography is well researched and draws upon a variety of sources. The author, Tracy Borman, does an excellent job of taking what could otherwise be dry, lifeless text and makes it into a relatable and accessible work of prose. The work sets up Matilda in context of her relations to her natal family as well as some of the political climate of the time. There are plenty of examples of other ruling females from the time, which I would be keen to know more about. However, this work seem to, at least at this point, have one major flaw: even though it is a work centered around Matilda, much of it is a revisit of historical thought on the men in her life, not on her. This may be due to scant evidence, but I was honestly excited to find out more about her, not William, not the Bayeux Tapestry, not the Battle of Hastings… her. While it is fascinating to see more work done on William that paints him in a more sympathetic light (instead of only a warlike and cruel invader), this central focus on this work is purportedly Matilda, not her husband. And while the author’s gift of prose is shown in describing the Battle of Hastings in detail (as well as setting up the context of the battle, in terms of Harold, the Oath, and the battles he’d fought against Tostig just before) that brings the battle to life and helps the reader to connect with the important event… where is Matilda? Oh, she’s at home, ruling Normandy. Doing a bang up job of it too, which Borman does a fantastic job of relating to the reader. Also interesting that while the Tapestry was rightfully mentioned in the book, there are other volumes that do a better job of describing in detail and research the various theories of where it was created, who commissioned it, and for what reasons. Andrew Bridgeford’s 1066: The Hidden History of the Bayeux Tapestry is one such work. Borman, after discussing the various origin stories of the Tapestry concludes that it most likely wasn’t Matilda, after all, who commissioned it or worked on it. So, then, why spend so much time and valuable space to bring it up?

Without the filler of work on William, Matilda’s family or the Tapestry, the book would probably be 3/4 of its final length. However, especially for a casual reader, this book is still a valuable and engaging read. As an introduction to the world of Anglo-Saxon and Norman England, this does a fantastic job of making the peoples, ideas and political climate of the time and place relatable and interesting.

Rating: 4.5/5 Owls

Why Owls? Because everyone is fond of owls, and they’re wise.